By Laura Carter //

In 1954 Sir James Spence and his research team at the Newcastle Royal Victoria Infirmary published A Thousand Families in Newcastle upon Tyne, the first volume in a series of works tracking the childhood health of a cohort of local children, all born in 1947. The Newcastle Thousand Families 1947 Birth Cohort (hereafter referred to as the 1000F study) began, much like the national 1946 birth cohort study, as a result of pre-war interests in maternity and infant care that were placed in sharper relief by the privations of wartime and the prospect of a National Health Service. Spence had posited in the 1930s that poor nourishment and health at home was to blame for outbreaks of infectious childhood disease in the city, and in May 1947 he began a study regularly visiting a representative sample of 1142 Newcastle families to find out more.[1]

Between 1947 and 1962 the 1000F study continued to track its members through primary and secondary school, and the survey began to rely more heavily on teachers and schools for obtaining their data in the late 1950s. Regular information was collected on social class, housing, height, weight, infections and illness, behaviour and criminality, school performance and cognitive testing, and home and leisure activities. Over this fifteen-year period, participant numbers dropped from the original 1142 to 967 after one year, 847 after five years, and 763 after fifteen years (in 1962).[2]

Encouraged by the success of our work on the original questionnaires of the national birth cohort studies, and thanks to advice from our colleague Sian Pooley at Oxford who has already worked on the 1000F study, we decided to investigate whether or not the data collection on these Newcastle families had left similar records. The current 1000F team, led by Mark Pearce and supported by Allison Lawson, were generous in granting us access to the original files of a sample of sixty individuals. Our Research Associate Laura Carter worked through the files this summer at the RVI in Newcastle.

We found a lot of material that was similar to that of the 1946 (national) birth cohort (aka the NSHD), such as school performance, job aspirations, and attitudes to school leaving. Other material was a bit different. For example, the 1000F study members were asked, at age 12, ‘If you could have three wishes to do with school, what would you wish for?’. This was more specific than the NSHD’s general ‘If you had 3 wishes, what would they be’ (asked at age 15). The Newcastle kids mainly wanted better facilities (‘I wish we could have the girls toilets in school’), less of the lessons they disliked, and more practical work, gym, and swimming (including the grammar and technical school kids). Worryingly, four boys in our sample wished to ‘blow up school’. Below is a ‘Wordle’ representing our sample’s ‘3 wishes’:

Although we were originally drawn to these sources for access to pupil voices, one of the most compelling aspects of the 1000F files were the parents’ surveys. In 1962, when the Newcastle children were age 15, and when many of them had already left school and started work, health visitors (and sometimes doctors) entered the family home to ask their parents questions about their child’s health and social progress, as well as to probe into parental attitudes on topics like raising the school leaving age to sixteen, and asking ‘At what age does mother consider children are at their most difficult stage?’

In these surveys, we find parents consistently resisting the tightly prescribed medical parameters of the study. Mothers expressed concerns over how minor ailments or lingering childhood illnesses might be affecting their child’s progress, or worse, their happiness. It was also an occasion for parents (and sometimes grandparents) to publicly sing the praises of children who had secured highly-sought after apprenticeships, or a job at a respectable department store like Fenwicks, ‘where they take an interest in their young staff’, as one mother put it.

Parents were often also keen to stress the gap between their generation and that of their offspring, and some documents were just as useful as sources on growing up in 1930s Newcastle. One mother was reported to have said ‘little about herself but did say if her husband had had the opportunities her sons failed to take he would be in a much better position’. Many of these families were still living in extreme poverty in Newcastle in the 1950s, as the city struggled to re-house its inner-city residents. When they found themselves in a regular dialogue with agents of the welfare state in their home, they reminded the experts that the physical, mental and social progress of their families was measured not in tables, scales and heart-rates, but in regrets and hopes passed from one generation to the next.

The same mother went on to explain that ‘…her husband was quite bright & some of the men now his bosses were not nearly as bright as he at school.’ Such comments reflect how, as we have found in many of our sources, the subjective value of education (or lack of) shifts across the life course. It is often when people are striving to ‘get on’ at work or become parents themselves that a recalibration of education’s worth takes place.

As well as providing these intimate family portraits, the 1000F study is of interest to us because it permits a focused look at secondary schooling in one urban area during a process of suburbanisation. As in many other postwar British cities, the population of inner-city Newcastle was changing in the 1950s, as families were either re-housed or sought their own, better housing on estates beyond and around the city limits. The total population of the city declined by 8% between 1951 and 1961. This meant high incidences of school changes for the cohort members, although this happened mostly during their primary school years: more than one third of the study children changed schools between 1952 and 1958.[3]

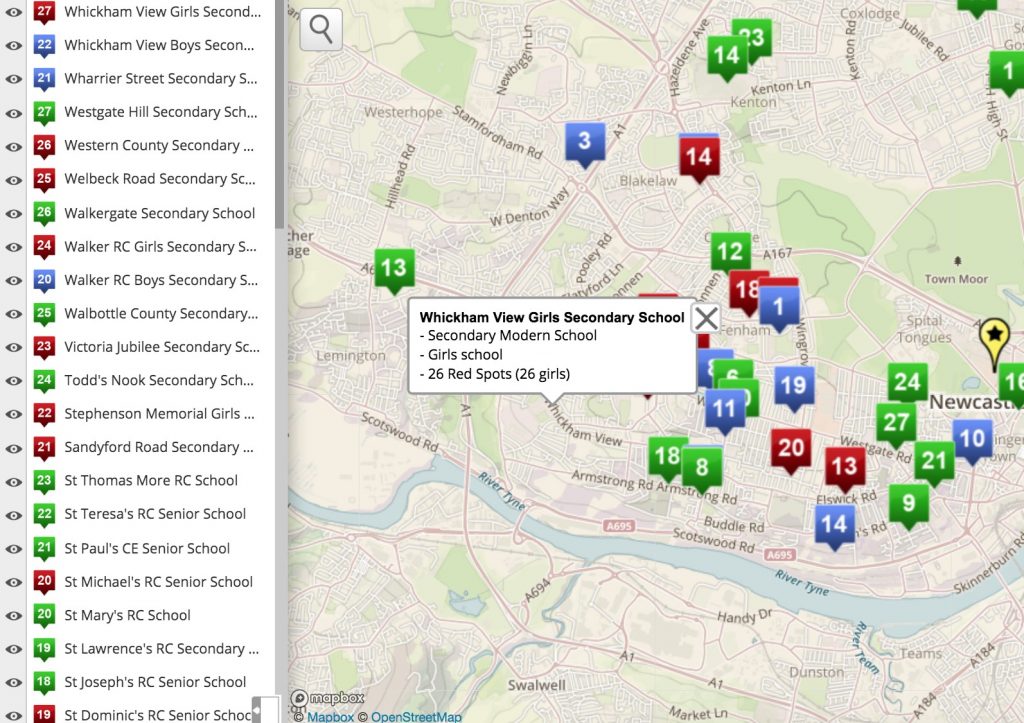

By the time the kids sat their ‘11-plus’ exams and reached secondary school in 1958, the population was far more spread out than had originally been planned. Moreover, school building struggled to keep up with these families on the move, resulting in many of the children in the study attending secondary modern schools that were essentially an extension of their junior schools, sometimes housed on the same site. These kinds of inequalities varied between regions and LEAs, new purpose-built secondary moderns (and eventually, comprehensives) were always far superior to makeshift alternatives. All told, 77 different secondary schools were recorded in the 1000F study records. We have created an interactive map showing their locations and distributions here.

Newcastle is also interesting for its bipartite, grammar technical schools. Some technical schools in the city, such as John Marley Technical, a boys’ school, offered both ‘12-plus’ and ‘13-plus’ entry options. The school them streamed its pupils based on their attainment, aptitude for languages vs. science, and age of entry. Pendower Technical High School for Girls on Fox & Hounds Lane, a sought-after option for many daughters, also offered courses in commercial skills such as shorthand, which secondary modern leavers could take up part time, after starting work.

Newcastle secondary schools in the 1960s, particularly the secondary moderns, also benefited from the initiative of the Northern Counties Technical Examinations Council which started offering a secondary-level examination in 1959, the ‘Northern Counties School Certificate Examination’. An alternative to the ‘O’ Level still valued by employers and parents, this school-leaving certificate promised access to higher-skilled jobs in the city. There was also a sprinkling of diverse options for independent education on offer in the city, ranging from Church High School (an elite day school for girls, competition for the city’s girls’ Direct Grant Grammar, Central Newcastle High School) to Gregg’s High School, a small and short-lived private school in Jesmond founded to teach the Gregg’s shorthand system.

As these examples suggest, looking closely at one city reveals the local peculiarities weaved into the tripartite system of education. It’s essential for our project that we get to grips with these differences up and down the country. But we’re doing so in a way that puts patchworks of schools and policies in the context of family, parent, and pupil experiences. The 1000F study is the ideal material for this type of endeavour. It allows us to overlay a top-down picture of education in the city with those qualitative, parental conversations happening inside homes. As we move into this second, regional, phase of our research project, we are finding that geography was a defining feature of the experience of secondary education in Britain after 1944.

We are grateful to Mark Pearce, Allison Lawson, and The Newcastle Thousand Families 1947 Birth Cohort based at the Sir James Spence Institute at the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle, for supporting this research

[1] F. J. W. Miller, S. D. M. Court, E. G. Knox, and S. Brandon, The school years in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1952-62: being a further contribution to the study of a thousand families (London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), pp. 1-3.

[2] Miller, The school years, pp. 10-4. M. S. Pearce, N. C. Unwin, L. Parker, and A. W. Craft, ‘Cohort Profile: The Newcastle Thousand Families 1947 Birth Cohort’, International Journal of Epidemiology (2008), give the 1962 (age 15) figure as 750.

[3] Miller, The school years, pp. 6-7.

Great work … born in 1947, being a girl from a working class family in Newcastle, when the headmistress of Pendower Technical High School informed my mother I would benefit from staying at school to study for A-levels my mother replied “My husband won’t allow her to”. My “purpose in life” as designed by my father, was to go out to work as soon as possible (in order to pay for my upkeep) and attend night classes if I wanted to improve my education, as I was “destined” to become a wife and mother, and should stay at home in order to look after my family. Having contracted polio when I was 4 years old his belief was it would be better I should die, rather than suffer any physical impairment for the remainder of my life. Fortunately this “lesson” in life served me well, in that I gave my three children the opportunity to go to university, instilled in them the benefits and rewards of a good education, in the hope they would fashion their own lives in a positive and fulfilling way. I would like to think our younger generation can choose their own path into adulthood … but am so aware of the north/south divide having spent most of my life living near Cambridge., now having returned to my northern roots.

I can assure you that in its early years the Northern Counties School Certificate was not a realistic alternative to the GCE. Employers barely recognised it other than for routine jobs for school leavers. That included low grade clerical work.

I am also sure that it was not officially linked in anyway to a qualification hierarchy. Its distinctions were not recognised as CSE grade one equivalents (perhaps they should have been) and in fact the Beloe report was not very enthusiastic about NCTEC, ULCI etc examinations for school children.

The examination did encourage some children to work harder and also get them into the habit of taking external examinations. Some of them took a mixture of GCE and Northern Counties.

Having said all that I am lead to believe the NCTEC did eventually arrange an examination for sixteen year olds that was broadly equivalent to GCE.

Dear Wilf,

Thank you very much for your insights, that’s very interesting, and we will certainly look into this further taking account of your perspective. If you have any reading suggestions on the NCTEC, please do send it our way.

Laura

Thank you for your good work which I found by chance.

I attended Pendower Technical High School from 1961 to 66. I so enjoyed my time there and had what I now see as a very good and broad education. Introduced me to language, literature, music and a wider view of the world as well as skills such as needlework and cookery I had confidence to attend Polytechnic and move to the London’s ‘Swinging Sixties. A well rounded education was an introductions to a wider world.