By Laura Carter

We are now six months into this research project, and it felt like the right time to tentatively air some ideas and instincts, with the conspicuous caveat that our proper archival research has not yet commenced. So, over the past few weeks we have given our first two papers at seminars and conferences in the UK and USA. Here I’ll offer some reflections on those experiences from a team and personal perspective.

We chose to write our first paper on the 1970s. Since writing our briefing papers in the autumn and after many team discussions, this decade seemed to be both the postwar decade with the most compelling narrative about secondary education, but also the most tangled and complex. The 1970s was the decade when the comprehensive school came of age; 1972 was the first year when more pupils were being educated in comprehensive than secondary modern schools, and by 1979 79% of pupils in England went to a comprehensive.

But the climax of comprehensivization as a structural change, with all of its political baggage and public debate, masked a whole raft of other complex changes also happening in education in the early 1970s. To name a few: the visible presence of ethnic minority youth in schools in some areas; concerns and fears about progressive education in practice; a culture shift in the independent sector towards technocratic and business career paths; the impact of gender politics on girls’ life choices; the raising of the school leaving age to 16 in 1972; parental activism against religious segregation in Northern Ireland; the ‘secularization’ of religious education.

Popular representations of secondary school kids in this decade often featured a rebellious, counter school culture, associated with the comprehensive schools but apparently present across both state and independent sectors, which was linked to broader social and moral panics fixated on young people. It seemed to us that such depictions functioned as a kind of crude shorthand for this vast and complex array of social, economic, and personal processes that were happening in classrooms. These processes would lay the foundations for material changes in aspiration and achievement for all social groups in the decades to come, seen in the greater uptake of school leaving qualifications (GCSE) and higher education. With all this in mind we wrote a methodological paper asking: how can we disaggregate the processes of social change that were occurring at the level of experience from this polarised picture of the comprehensive school in the 1970s?

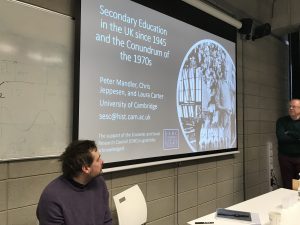

Our first outing was to the University of Lincoln’s History and Heritage seminar on 14 March 2018, where we were generously hosted by Kate Hill and colleagues. Presenting together at Lincoln gave us the chance to not only trial some content in front of a discerning audience, but also practice writing and delivering a tripartite (excuse the pun) paper. Peter opened with some comments about the motivations for the project, Chris sketched out the decade in educational terms and gave a flavour of the representation of ethnic minority secondary school pupils in the media and on television in the 1970s, and I talked about three possible source types we might use to access these pupils’ actual experiences: HMI reports, social surveys, and oral evidence.

The sources I looked at for thinking about the experience of non-white pupils in the 1970s highlighted the importance of streaming to their time at secondary school. Even in non-selective comprehensive schools, the practice of streaming kids could simply reproduce the bipartite or tripartite model and limit the social mixing that was one of the comprehensive school’s USPs. South Asian and especially Afro-Caribbean British school pupils often found themselves in the lower streams as a result of English language deficiencies, ‘culture shock’, and institutional racism.

We had a productive discussion in the Q&A at Lincoln about streaming and subject setting by ability, which came later in the 1970s. Our questioners reminded us that we need to be attentive to the variety of streaming and setting practices, another feature of the regional and urban/rural unevenness of secondary education in the 1970s. Clearly streaming did reproduce the grammar/secondary modern divide in some comprehensive schools, as sociologists pointed out at the time, and this was inflected by racial stratification in areas like the Midlands, London, and the North West.

But mixed-ability teaching did also persist in a significant number of comprehensives (finding out precisely what proportion is now high our to do list). There may be a more optimistic story to tell here about this model paving the way for a more collectivist and democratic school ethos, leading to the increase in further and higher education participation rates in the 1980s. Gender must be a missing piece of the puzzle here, and likely our honing-in on race (most of the sources for which dealt only with boys) obscured the picture. One of my next jobs is to survey the vast literature on girls’/boys’ secondary education in postwar Britain and draw out the most important themes and questions in a briefing paper on gender, which we will post here on our website.

The week following Lincoln I travelled solo to California to attend the Pacific Coast Conference on British Studies at UC Santa Barbara, 23-25 March 2018. Here I presented some of the same material on sources for unpacking the 1970s on a panel with speakers from UC Berkeley who spoke about deindustrialisation in 1970s Belfast, the affective economies of airports and women’s work in the postwar period, and the discourse of ‘working parents’ in the late century.

Questions and discussions revealed some productive overlaps and some diversions. Christopher Lawson’s work on how working-class communities responded to structural deindustrialisation in Northern Ireland reminded me of our need to capture the highly local dialogues that were occurring between local employers and secondary schools, in a period when most leavers did not gain qualifications or go on to higher education. We are hopeful that these patterns can be picked up from HMI reports, which often featured sections on school-level careers advice as it existed in the 1970s. From there we might piece together accounts of what individuals thought their secondary education was for in different regions.

We were also asked about locating affect in the archive, picking up on a common theme of many of the post-1945 papers at PCCBS. Here I had my trepidations; are we trying to find out how school made people feel? Is the emotional landscape of school manufactured or organic, and is this actually a change that happens within our period? I’ve no doubt that we will come across this in our sources: aspiration, disappointment, trauma, and fulfilment are all feelings surely evoked by the experience of secondary education across its stages. But we need to do more thinking about how far we are trying to tell an emotional history of schooling and how this is different from an experiential one.

Lifting my head up from the books for a couple of weeks and talking to people at both events reminded me of one of the major challenges facing us on this project: staying focused on our questions. Although this is surely true of all major research projects, secondary education in postwar Britain in particular is an historical arena upon which historians of all castes and creeds readily project their own topics and questions. This is brilliant and stimulating, but it also creates a thousand potential new roads to follow including (but not limited to): the history of disability; the history of sexual exploitation in schools; school dinners and food policy; teachers’ histories; youth culture and friendship; the history of parenting. I hope we can touch upon all of these things, whilst still achieving in the end what we set out to do: write a history of the changing generational experience of secondary education in the UK since 1945. This will require discipline and creativity in equal measure!