By Peter Mandler

It’s not surprising that the centenary of the Fisher Act has gone almost unnoticed. There are certainly other centenaries more worthy of public attention – the end of the First World War, the achievement of women’s suffrage. And the Fisher Act has perhaps deservedly lost traction on public memory in the wake of the Butler Act of 1944, which made secondary education universal. No other piece of educational legislation has come even close to lodging in popular consciousness.

But the Fisher Act hasn’t even stirred the hearts of historians, much. While it may have represented a brief flash of idealism at the end of the First World War, its implementation was botched and delayed and consequently most historians have paid it little respect. They have tended to see it as a continuation of prewar trends – an incremental extension of educational opportunity only by those local authorities that cared most – or as a conservative muddle shaped by competing and irreconcilable interests. In any case, governments after 1918 picked off its more innovative provisions one by one, in the interests of economy or perhaps just lack of interest, so that the Fisher Act appears to have been a dead letter. It remained for the Butler Act in 1944 to reintroduce most of its provisions and deliver on them.

What did the Fisher Act purport to do? It raised the school-leaving age to 14 and encouraged local authorities to move more of their elementary-schooled students to secondary school. It enabled local authorities to offer maintenance grants to students continuing to secondary school to encourage working-class take-up. And it mandated part-time ‘continuation schools’ after the age of 14 for those who had left full-time education for work. The idea was to provide a ‘broad highway’ or at least a ‘ladder’ of opportunity for all regardless of ability to pay. But each of these provisions was curtailed or postponed in the years immediately after 1918. Even the raising of the school-leaving age was postponed until after a new act in 1921. The ‘broad highway’ did not materialize and even the ‘ladder’ was not much extended. The proportion of elementary-school students who progressed to secondaries only rose from 10% in 1920 to 14% in 1938. It would take the Butler Act to mandate ‘secondary education for all’.

What, then, is there to celebrate – or even to mark – in the Fisher Act? Seen in the longer-term context of educational expansion and reform, that immediate postwar moment did bring secondary education onto the national agenda for the first time. In the decade of the 1910s – even during the war – the demand for secondary education grew dramatically, such that the number of free places for elementary-school students seeking to progress was plainly seen to be inadequate. The trade union movement began to throw its weight behind ‘secondary education for all’; the exception, the textile unions, who defended adolescent labour, has been given more attention than it deserves, though its representatives were certainly noisy. Fisher himself noted the warm reception he received on his educational tours during the last years of the war: ‘The prospect of wider opportunities which the new plan for education might open to the disinherited filled them with enthusiasm’. ‘Secondary education for all’ took on some of the same wartime aura enjoyed by ‘homes for heroes’ – a war aim, deemed a just reward to the mass of the people for their national service – and although both demands were suffocated by postwar austerity they made an enduring mark on popular consciousness.

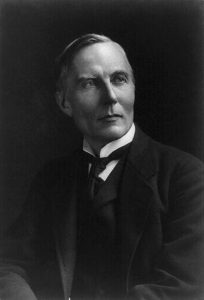

Right: Herbert Fisher (1865-1940), from the George Grantham Bain collection at the Library of Congress. No known copyright.

Most importantly – and here the coincidence of the Fisher Act not only with women’s suffrage but with universal male suffrage is significant – advocates for secondary education for all in 1918 created a powerful link between education and democratic citizenship. Arguments for extending educational opportunity had hitherto been made more pragmatically on the basis of national efficiency and productivity. Analogies with Germany had been rife – Britain needed to raise the school-leaving age to keep up in the race for international economic supremacy. In the atmosphere of 1918, however, arguments shifted. Germany was not such an obviously good comparator. The United States, with its ‘common schools’ and long tradition of universal suffrage (at least for white men), was a much better one. Liberals and socialists alike were now advocating for universal provision of secondary education as a right. 75 of them voted for unsuccessful amendments to the bill dropping the continuation schools and enable local authorities to require full-time schooling to 16. Only this real move to secondary education for all, its advocates argued, would end the ‘class system’ of education that then prevailed.

These voices were obviously in a minority in 1918. But they set a new tone. They provided a democratic basis for collaboration between ‘idealist’ Liberals and Labour which led to many of the former joining Labour in the ensuing few years; thus one of the fruits of the Fisher Act was to help establish the Labour party as the main progressive voice in the interwar years. They established a link between education and citizenship in people’s minds that would recur with even greater strength during the next world war. And they began to develop a line of democratic – rather than utilitarian or meritocratic – thinking about secondary education that would continue to blossom in the post-1945 world characterised not only by universal suffrage but also by universal provision in the welfare state and ideas of ‘social citizenship’. Thus from the point of view of our project, examining the age of universal secondary education, the Fisher Act might serve as a key cultural and ideological starting-point.

The Day Continuation Schools continued after the Geddes Axe and thrived in areas such as Manchester where the LEA was progressive into the 1930s and beyond. You don’t mention the Ex- Servicemen’s Scheme which, Fisher thought, was one of the great achievements of the 1918 Act (in providing access to British Universities for working class students) . See his autobiography.

Sorry Peter, My comment seems to have rebounded. I hope you see it. David.

As the Fisher Act provides the right to schooling for teenagers it is very important for the history of childhood, and also the speech of Earl Lytton on 23rd July 1918 and his leadership of the New Ideals in Education community creating schools ‘to liberate the child’, creating the modern child centred primary school, but failing to have much effect on the exam focused, academic, curriculum defined secondary schools.

I hope to be celebrating these events and community with schools, teachers and children in London.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Mpg_pNABq4krz2zRx-wqYrQRbgRYrWnh/view?usp=sharing