By Chris Jeppesen

I am writing this while humming along as next door’s builders belt-out Three Lions (Football’s Coming Home); with excitement levels soaring in anticipation of England men’s first appearance in a World Cup semi-final in twenty-eight years, now seems likely to be the only occasion in which it is even remotely appropriate to shoehorn football into the project blog! Over the last month, the SESC team have juggled trying to watch as much football as humanly possible with preparing to start archival research on the three postwar cohort studies (started in 1946, 1958, and 1970). This is something we will write more on in the autumn but, in short, we are using the studies, which follow nearly every child born during a single week in each respective year through their life course, to explore one of the project’s central research questions: how has the experience of education differed for successive generations growing-up after 1945?

Thinking about this, while the World Cup has been on in the background, has also made me wonder how the educational profile of England footballers have changed over the same period. England have reached the World Cup semi-finals on two previous occasions, in 1966 and 1990, with these three squads, each roughly a generation apart, providing an interesting means to compare how changing educational structures and attitudes have affected the pathways of future England internationals into professional football. Exploring this has taken me back to many of the key themes we have been thinking about as a team since last October. In these players’ educational careers, we see, for example, the effects of selection through the 11-plus, the way attitudes towards social class shaped the experience of school, the uncertainties of transitioning from school to work in a contracting labour market, and some of the challenges faced by non-white pupils as Britain became a multiracial society. All these themes, and more, can be read about in more detail in our project briefing papers, available on the website Resources page.

1966

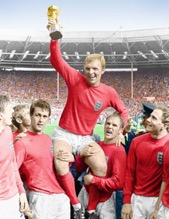

England’s solitary World Cup triumph to date came on home turf in the summer of 1966. Watched by almost 97,000 fans inside Wembley and a record television audience of 32 million people, victory over West Germany arrived thanks to goals from two West Ham players who had grown-up playing schoolboy football in Essex Secondary Modern Schools, before joining their local club as apprentices.

With an average age of 26, many of the 22-man squad had been born during the decade leading-up to the 1944 Education Act, meaning they became some of the first recipients of compulsory, free secondary education in England. At 31 the oldest members of the squad, Ray Wilson and Ron Flowers, had made the transition to secondary school in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the same year that the youngest, 21-year-old Alan Ball, was born. By 1966 all had proceeded through the tripartite system, in which children were sorted at age-11 on the basis of a competitive exam to determine whether they would attend a secondary modern, grammar or, more rarely, a technical school.

Professional football’s nineteenth century roots lie in the industrial towns of the north and Midlands. By the interwar period the sport had acquired a mass following within working class communities, with the biggest clubs often attracting attendances of over 60,000 each week. It is perhaps unsurprising then that all of the squad in 1966 came from staunchly working class backgrounds. The players’ fathers included coal miners, publicans, grocers, pipe fitters, London Underground drivers, and even an undertaker, while many also had mothers who worked in factories or as cooks. Several were the sons of Irish migrants and one of Swiss parents who owned a café on the south coast. In the mid-1960s, football remained a sport dominated by white players and fans on the terraces. Viv Anderson became the first black player to win a senior England cap 12 years later in 1978.

While the squad’s social profile may have been narrow, the schools attended were more varied. Seven passed the 11-plus and attended grammar school, which at 31% of the squad represented a higher proportion than the national average at this time. In Essex, Bobby Moore, the man who would lift the World Cup, attended Tom Hood Grammar School, where he also played in a representative London grammar school side, while George Eastham and Jimmy Armfield played schoolboy football together at Arnold School, a direct grant grammar in Blackpool. Interestingly, striker Roger Hunt made the unusual transfer from Culceth Secondary Modern to Leigh Grammar having initially failed the 11-plus.

For the Charlton brothers, Bobby and Jack, differing fortunes at the 11-plus led to divergent school experiences. Bobby went to Bedlington Grammar before joining Manchester United as an apprentice, while Jack attended Hirst Park Secondary Modern, leaving at 15 for a job in the same coal mine as his father and only becoming a professional footballer with Leeds eighteen months later. In recalling their school years, several of the grammar boys recounted facing class-based hostility from schools preoccupied with rugby or, for Alan Ball, an unsympathetic Headmaster who was outraged when he chose to play in a local club match over the school team that he captained.

For those like Gerry Byrne, Ian Callaghan, and John Connelly, who came from the North West’s large Irish community, voluntary Catholic schools provided an alternative to the tripartite system. As discussed in our briefing paper on religion and education, these schools sat outside of LEA control, drawing on the support of the church and local community, and often had a reputation for providing a steady stream of top players to local clubs. The remaining players attended secondary moderns. These schools differed markedly in character and facilities. Some were formed out of old all-age elementary schools and occupied cramped sites in the middle of cities, while others were built in the years after the war on green field sites with lots of space for football pitches. Many were successful sportsmen at school and later recalled with affection PE masters who bore a striking similarity to Brian Glover’s famous depiction in the film Kes.

Several did well academically. Jimmy Greaves gained his School Certificate whilst Head Boy at Kingswood School, Dagenham and would have joined The Times as a trainee reporter if he hadn’t signed for Chelsea aged-15. Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst both obtained four O-level passes, the latter at Rainsford Secondary Modern, while Jimmy Armfield was the only one to gain his Higher School Certificate, which required him to remain at school until 17.

Like the majority of pupils at this time, however, most of the squad left school at the earliest opportunity once they reached age 15. At a time when footballers’ wages were capped at £20 p/w, many parents were sceptical that football represented a sensible career choice and encouraged their sons to learn a trade instead, which often promised more lucrative and secure prospects. Many of the older players started apprenticeships or entered other manual jobs upon leaving school, while continuing to play football at an amateur level. For example, Ray Wilson and Ron Flowers both became apprentice railwaymen. Terry Paine, who later played for Southampton, worked as a coach builder in British Rail’s Eastleigh depot, while Gordon Banks credited his upper body strength to his time spent as a coal bagger after leaving school at 15. Right back George Cohen, left Fulham Central School with an O-Level in technical drawing for an apprenticeship as an electrical fitter, and reserve goalkeeper Ron Springett started an apprenticeship as a motor mechanic before being despatched to Egypt on National Service during the Suez Crisis. It was more common for the younger members of the squad, leaving school in the late-1950s, to sign straight-on as apprentices with professional clubs. Apprenticeships rarely bestowed immediate glamour and status, however. Teenage players were expected to work as ground staff or in the club offices and often had to keep up second jobs outside of football to supplement their low pay. Even when he was England captain in the early 1960s, Jimmy Armfield had to augment his income by working as a journalist in the summer months because his wages dropped by more than half during the close-season.

England’s success in 1966 is often credited with initiating a profound shift in football’s culture. For the generation of school children watching on their new televisions as Bobby Moore was carried aloft holding the Jules Rimet trophy, the sport was starting to take-on the aura of glamour and celebrity that has become so familiar. The expansion of secondary education and spread of comprehensive schools also had more practical benefits as more and more boys (and it is important to note access remained highly gendered) had the chance to play themselves. This generation not only supplied the players who travelled to Italy in 1990 but also the journalists, television producers, and professionals who, in the assessment of the writer William McIllvanney, transformed football from ‘working class theatre into middle class cabaret’.

1990

Perhaps best remembered for Gazza’s tears, England’s penalty shoot-out defeat to West Germany in Turin ended hopes of a second World Cup success but, as Joe Moran observes, was also the moment many commentators have identified as being when the sport entered its modern age.

The backgrounds of the 1990 squad, however, don’t immediately signal to the profound changes that were to follow over the following decades. Many came from similarly working class areas and families as their 1966 counterparts. Most of the 22 players, born between the late-1950s and mid-1960s, experienced comprehensivization first hand. Born in 1957, England captain, Bryan Robson, started secondary school at Birtley South Secondary Modern but moved halfway through secondary school to the area’s new comprehensive, Lord Lawson of Beamish School. Gary Lineker was the only member of the squad to have attended a grammar school, the City of Leicester Boys’ School, but had to move-in temporarily with his grandmother so that he could get into a school that played football.

This generation of England players better reflected the nation’s growing racial diversity. The parents of defenders Paul Parker and Des Walker had both settled in East London after arriving from Jamaica, where their sons were born and attended local comprehensives. After spending his early childhood in Jamaica, John Barnes arrived in England when his father, a colonel in the Jamaican Army, was posted to the embassy in London. He first attended St Marylebone Grammar, a selective school in west London, and when this closed moved to Haverstock Comprehensive in Camden to join the Sixth Form. As the 1981 Rampton Report into the experience of ‘West Indian Children in our Schools’ made clear, secondary education was often an alienating experience characterized by institutional racism, with many black pupils crudely stereotyped as good at sport but poor academically.

Following the Raising of the School Leaving Age [ROSLA] to 16 in 1972, almost all of the squad remained at school longer than their 1966 predecessors; however, many later recalled that school’s only attraction lay in playing sport and that they left as soon as they could, often without qualifications. A few did stay longer. Terry Butcher gained a Maths A-level and was offered a place at Trent Polytechnic to study surveying, but abandoned these plans to join Ipswich, while his centre back partner Mark Wright stayed-on at school in order to become a PE teacher until he was offered a contract at Oxford United. Eighteen of the squad moved straight from school to sign full time Apprenticeship contracts with professional clubs. Even so, several faced a harder route to footballing success and had to enter the youth labour market, which in the late-1970s and 80s could be difficult. Stuart Pearce trained as an electrician whilst playing amateur football, even continuing to advertise his services in the Nottingham Forest matchday programme once he had started playing in the First Division. Chris Waddle, who missed the decisive penalty in the semi-final, worked in a North East food processing plant before signing for Newcastle at 19. Steve Bull, the only player not with a top-flight club in 1990, supported himself as an amateur footballer with a series of low paid factory and manual jobs in the Black Country until he signed his first professional contract aged 20.

2018

So, what of today’s squad? Only six members of the squad had been born when England lost on penalties in 1990, and all have grown-up in a profoundly changed footballing landscape, dominated by the Premier League, 24-hour coverage, social media, and extraordinary amounts of money. At the age of 17, Ruben Loftus-Cheek signed a contract worth £1.7million with Chelsea; Raheem Stirling’s £49million pound transfer from Liverpool to Manchester City made him the most expensive 20 year old ever, but it was his move from QPR to Liverpool for £5million five years earlier that set a world record for a teenager. The new financial structures of elite professional football have profoundly changed the relationship between clubs, schools, and young players. With the exception of Jamie Vardy who played non-league football into his 20s, all of the current squad have been in elite Youth Academies since their early teens, with several having signed for Premier League clubs as young as 8. The fragmentation of the education system following Thatcher’s governments and New Labour’s drive to increase parental choice and raise standards by allowing more schools to opt out of LEA control has given football clubs more opportunity to involve themselves directly in local schools. For instance, Marcus Rashford and Fabian Delph both attended schools that had formal link-ups with their clubs, Manchester United and Leeds United respectively. Goalkeeper Nick Pope is the only player in all three squads to have attended an independent school; however, he is only the latest in a growing number of England internationals, including Frank Lampard, to have been educated in the private sector. Most players sat their GCSEs before joining their clubs fulltime, with Harry Maguire and Danny Welbeck both excelling at school. It is important, however, not to exaggerate the cleavages within the modern game. Many of the family backgrounds of the current squad differ little from the previous two: they tend to be overwhelmingly working class and educated in local state schools. More have grown-up in households where their mum is the primary breadwinner, which reflects changing family structures. This is also a more diverse squad than ever before, with players of colour coming from cities and towns across England.

As manager Gareth Southgate recently said: ‘We’re a team with our diversity and our youth that represent modern England’. These players are also products of a changing education system, one that has become more democratic over the course of the late twentieth century. Their experience of school continues to reflect inequalities of class and race, just as it did for the 1966 and 1990 squads, but it also exhibits changing values and possibilities that, as Southgate has alluded to, can also been seen to say something heartening about the relationship between education and social change in Britain after 1945.

A small correction to an interesting article:

Noone in the UK – schoolchildren or adults- watched the 1966 world cup final ‘on their new colour televisions’. Colour broadcasting did not begin until Wimbledon in summer 1967. Even by the time of the Mexico Olympics in 1968 when more colour programmes were being broadcast (but only on BBC2) , colour TV sets were rare, very expensive, and a major status symbol.

The colour footage seen of the 1966 Final was from a cinema film released in late 1966

Many thanks for your correction, Graham – we have edited the post!

Interesting slant, but I found many of the 1950’s / 1960’s players evolved from army teams during national service. My own father indeed played with the late, great John Charles in the 1953 army cup final. In the limited access i have been given that appears to have been the case in many previous cup finals, so may I suggest a Chapter 2 ?