By Harry Gibbins

Harry is a third year undergraduate student in History at Selwyn College, Cambridge, working on a dissertation with Dr Chris Jeppesen entitled The Experience of Secondary School Amalgamation in North-West England, 1965-90

SESC, for me, could not have been launched at a better time. With my final year as a history undergraduate looming on the horizon, I was considering a number of possible topics for my dissertation. When I learned that a research project on education in post-war Britain had just begun in the History Faculty – which would make available a range of interesting and useful resources – this decision was made significantly easier. Fast forward several months, and I am now working on a dissertation, supervised by SESC Research Associate Dr Chris Jeppesen, which examines how pupils, parents, and teachers responded to the amalgamation of secondary schools in the North West of England between 1965 and 1990.

This is a topic that reflects my own secondary school experience, as well as my academic interests. My secondary school was the product of a merger in 1987 between two schools located within a mile of each other, one a former secondary modern and the other a former grammar, though both turned comprehensive in 1979. To this day, the school remains split across the two sites, with pupils changing sites at fourteen.

As a first-year student at Cambridge, one of the readings which made the greatest impression on me was Selina Todd’s account of working-class pupils’ experiences in grammar schools and secondary moderns, for which she drew on mid-century social surveys and oral history interviews.[1]

I was keen to incorporate an oral history component into my own dissertation research, and, as such, spent part of my summer conducting interviews with people who had experienced amalgamation first hand, either as teachers or as pupils. In the rest of this post, I draw upon this material to sketch how the process of amalgamation has been remembered by my interviewees.

The interviews – ranging between 45 and 90 minutes in length – yielded rich and diverse accounts of how school amalgamation affected different individuals in different ways. As one former teacher summarised, ‘it was a hectic time, it was a busy time, it was an emotional time’, with some benefitting and others losing out amid the upheaval of a school merger. For some, the transition was much more sudden: ‘I don’t think we knew really what we were in for’, admitted one respondent.

Even though amalgamating schools often took pupils from the same neighbourhoods, the sense of stepping into the unknown could fuel rumours about those from the ‘other school’. One former secondary modern school pupil recalled expecting her counterparts from a former grammar school to be ‘snobby’ about having been to the ‘superior establishment’. Another respondent from the other side of the divide, meanwhile, recalled similar misgivings: ‘we thought they were going to be monsters; we thought they were going to hate us; we thought they were going to bully us.’ The extent to which schools tried to soften this change for pupils varied greatly. One respondent recalled being kept as ‘a grammar school bubble in a developing comprehensive school’ as part of an attempt – with mixed success – to provide continuity for older pupils.

Above: Liverpool Echo, 26 September 1972. Photograph of the student council of a newly-amalgamated school, from an article titled ‘Joining Two Schools and Two Traditions’

If preparing pupils for amalgamation was neglected, this was largely because the process of preparing staff was an even more complex operation. Senior staff would have to reapply for their jobs and compete against their counterparts, which, as one former teacher was keen to reinforce, caused ‘a lot of distress’ in the staff room. This process was sometimes so fraught that it resulted in a total breakdown of relations: one former teacher recalled how a headteacher was so angry about missing out on the new headship that he refused to allow his replacement onto the site. Another recalled that a conflict between two staff competing for a Head of Department post turned so ‘nasty’ that one of the pair – a ‘brilliant mind’ and highly-respected teacher – quit the profession altogether.

Of course, secondary school amalgamation was not just about moving to a comprehensive system: it also involved creating coeducational schools. This change often brought new opportunities for pupils from which they had previously been excluded because of their gender. For instance, a former cookery teacher recalled taking on a class of 15-year-old boys for the first time: ‘They’d never done Food Tech before, and, to be honest, they loved it. It was a delight to teach them.’ Another teacher, who had worked in a boys’ secondary modern, was involved in the rolling out of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award scheme to girls for the first time when his school amalgamated.

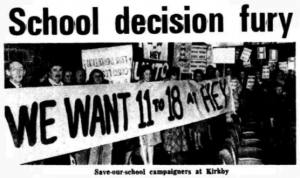

Left: Liverpool Echo, 28 February 1980. Article about parents protesting a school closure (as part of a wider amalgamation process) at a Knowsley Council meeting.

That said, coeducational mergers did not always end gendered exclusion. ‘Some of the girls in the A Level Art group actually tried to get permission to go and work in Metalwork, to do some jewellery,’ a respondent who entered a newly-amalgamated school as a newly-qualified teacher recalled, ‘and they weren’t allowed’. Indeed, unless carefully managed, coeducational mergers could have a negative impact, especially on girls. ‘I just remember the boys always being able to dominate the conversation,’ recalled a former pupil whose girls’ technical school amalgamated with its all-male neighbour. ‘You lost your confidence in the classroom because you were competing with the boys, and the girls just took a back seat.’

Though the examples above demonstrate the variety of secondary school amalgamation across the region, there was one thing which most mergers had in common: they produced a bigger school. This, of course, had its pros and cons. Former teachers commented frequently on the curricular and extra-curricular opportunities generated for pupils by being in a larger school. This, however, was balanced by the loss of a sense of community which had existed in smaller schools. ‘A grey pupil would become greyer’, admitted one ex-grammar school teacher. ‘You could walk past pupils and not know who they were, which I don’t think’s good.’ Pupils also picked up on this. ‘I was just a number, I wasn’t a person any more’, recalled one who experienced a merger that created a ten form-entry comprehensive. ‘I didn’t feel they invested as much interest in you,’ agreed another pupil from a similar amalgamation, ‘So you could drift a little bit more, if that’s the right way of putting it.’

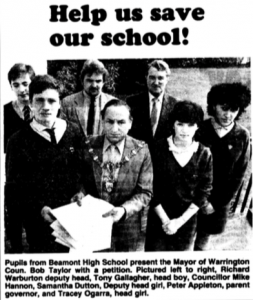

Right: Liverpool Echo, 16 March 1984. Article about a petition signed by pupils to protest a planned amalgamation.

These interviews are only one element of my wider research, and over the coming months I will visit more archival collections to help place these memories in a broader context of school restructuring. Even so, the interviews clearly illustrate that despite variations between Local Education Authorities – and indeed between schools – amalgamation tended to have a profound impact on the day-to-day rhythms of school life. However, since schools are diverse communities, this experience of change could differ widely depending on gender, background, and personality. In exploring these previously unheard insights, my research will offer an important new perspective on how the restructuring of secondary education in the North West also reshaped the everyday experience of school for pupils and teachers alike.

[1] Selina Todd, The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class (London: John Murray, 2014), pp. 216-35.

late 1950’s buildings that had extensive playing fields, serving a modern post war housing estate.

The Grammar school effectively ‘took over’ the Secondary Modern School. The senior staff were all from the Grammar School, the older pupils were accommodated in the former Grammar school buildings, the ethos in the school was the Grammar School ethos, and even the uniform remained 90% of the Grammar School.

I remember when we went comprehensive and the Upper School (PGS) was in Lower School (OSM) like a shot asset stripping the place – teams of us were led over and returned with vast amount of materials leaving lower school devoid of much essential equipment. If anyone had a right to complain it was the OSM students who remained in a school bereft of essential equipment that, quite frankly, spent a lot of time never being used but decorated window sills at Upper School. The older Secondary pupils stayed at Lower School and huge amount of the curriculum (CSE General Science for example) must have been undeliverable because essential equipment had been moved to Upper School.

There were attempts to integrate the school. For example one year for sports day the whole Upper school emptied and trecked the quarter mile to the Lower School site. But this only happened once. The uniform became identical across the school. Some staff taught in both buildings – but not in timetabled blocks. Staff would have to commute between buildings outside of lunch and break times. This meant staff either left lower school lessons early or were late to Upper school lessons – either way there was a time when staff were consistently late for lessons leaving large numbers of pupils not supervised. It took a while for the school to realise that it would be better to timetable staff for a morning or afternoon session at a single site, thus meaning staff travel could be at lunch time and no teaching groups were left unsupervised.

A final point comes from the sixth form. I remember vividly looking around an A level English class, and realising that half of the pupils were originally from OSM. I wondered at the time if they would have had the opportunity to complete A levels if there had been no comprehensive re-organisation. And it became clear to me that the oft vaunted claims about academic standards of Grammar schools were simply not true – many secondary modern pupils, with the right environment and teaching, were perfectly capable of academic excellence. All that was missing was the chance..