By Laura Carter

Over the past month I have been travelling around England and Wales visiting Local Authority (LA) archives – Glamorgan, Bristol, Tyne and Wear, and North Yorkshire – trying to get a sense of the types of material on secondary education that these repositories hold, how accessible they are, and how we might use them for our project during 2019. Within the team we have always had a strong sense that we want to use records of individual secondary schools held in LA archives, but we didn’t have much idea of how uniform such collections might be, or what they would yield for our purpose of understanding the experience of secondary education. I had used one, very rich collection of sources relating to a boys’ secondary modern school before (used in this published article), but I knew such finds were far from the norm.

Above: Interior of Tyne and Wear Archives, Newcastle-upon-Tyne

This blog post is a rough guide to what I found during my travels, which may be useful to other historians working education and social change in post-1945 Britain seeking to make the most of these under-used, but often complex, sources for social history.

Planning a trip and source accessibility

In planning each archive visit I spent a long time researching their online catalogues to get a clear sense of the structure of the education collections (for example, how administrative records, such as Education Committee minutes, and school records, such as log books, are organised distinctly). I also spoke to each of the archivists on the phone about the accessibility of material listed as closed under Data Protection legislation in their catalogues. This latter point is quite important: you will most likely find that a lot of post-1945 school material is by default closed under the ‘100-year rule.’ This does not always mean you cannot see it, but it might mean needing to explain your research more carefully in advance of a visit, and signing a Data Protection form confirming you will adhere to keeping all sensitive personal information confidential in your note-taking and outputs.

The introduction of GDPR in May 2018 has naturally triggered reviews and procedure updates in a lot of archives, and some repositories are more cautious than before. But the UK’s implementation of GDPR has adopted all research exemptions and is actually quite favourable towards the retention and use of historical data for research through its concept of ‘archiving in the public interest’, as long as the data in question is stored and shared according to its guidelines (for more on this, see The National Archive’s GDPR FAQs). So GDPR should not, in theory, present a barrier to research on school records. But you may find you have more administrative hoops to jump through, so leave plenty of time to do so as hard-pressed LA archives find the time and resources to update their policies and handle your request. We found it useful to prepare an ‘Ethics and data security statement’ and an ‘Archives protocol’ for our project, which we can share with archivists and administrators whenever queries about access arise.

What types of sources relating to UK secondary schools can you expect to find in LA archives?

All state-maintained UK schools have had a statutory requirement to keep official records throughout the twentieth century. These include but are not limited to: admission registers, attendance registers, punishment books, meeting minutes, and log books.

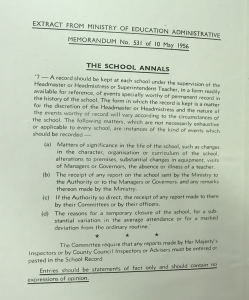

Log books: Log books are by far the most common and most likely source to survive, because they were the only record that schools had to preserve for ‘the whole life of the school’. Their value for research on school cultures and the history of childhood in Britain since 1945 has been demonstrated recently by a PhD thesis by Andrew Burchell on school discipline and Laura Tisdall’s forthcoming book on progressive education. Board of Education Administrative Memorandum No. 48, ‘School Records’, stated that school log books should be completed ‘under the supervision of the Head Master or Head Mistress or Superintendent Teacher’. They were instructed to record ‘Events specially worthy of record for future reference or for other reasons, such as alterations to premises, introduction of new books and apparatus or of new courses of instruction, visits of Managers or Governors, the absence or illness of a teacher.’ This guidance was updated by Ministry of Education Administrative Memorandum No. 531 in May 1956, ‘The School Annals’, compelling schools to record ‘matters of significance in the life of the school’ and noting that ‘Entries should be statements of fact only and should contain no expressions of opinion.’

Left: Ministry of Education Administrative Memorandum No. 531, ‘The School Annals’, May 1956.

As these stipulations indicate, log books are written from the ‘expert’ perspective of the Headteacher and are mostly descriptive. The majority of the ones I looked at were for secondary modern schools, as these are usually the only sources relating to this school type that are extant. They varied in detail and liveliness. Most were simply administrative records with one-line descriptions of staff absences, visits from external people, details of school openings and closures etc. I learnt that schools in the 1950s and 1960s were closed for General Election days, were burgled far more than I imagined, and that dental inspections were carried out pretty frequently! A couple were more colourful and had extra papers stuck in, and entries gave a little more flavour of the day-to-day life of the school. The 1970s comprehensive school log books I looked at were more fruitful than the 1960s secondary modern ones, perhaps because they were often penned by an enthusiastic new Head, keen to demonstrate the success of this new school type to external readers.

Punishment books: These sources are much less common than the log books; they were a statutory requirement but schools were not required to keep them for longer than three years after completion, so it seems likely that most were destroyed. I only managed to look at one from the post-1945 period, although I found many from the interwar years in catalogue searches. Each double page contained the following columns: date, name of scholar, offence, nature and extent of punishment, by whom inflicted, initials of Head Teacher. These sources are quite illuminating on issues of pupil-staff interactions and on gender. But, like the log books, are not much use in isolation from the wider context of the school in question.

Above: School ‘Punishment book’ title page, 1930s.

Leavers records: Leavers records are less common than log books but more common than punishment books. They vary in format. I looked at a few different types: a leavers book, a set of pupil record cards, and a set of pupil testimonials. The leavers book recorded for each pupil: Term/form, Name/gender, Date of birth, Regularity, Punctuality, Diligence, Conduct, Special aptitudes, General remarks. The pupil testimonials, from a comprehensive school, were actual certificates containing half a page of prose describing the pupil. They also recorded when they entered and left the school, what exam courses they followed, and a couple of paragraphs on their nature, behaviour, extra-curricular activities, and contributions to the school. Like most of the more niche sources I found, these kinds of records seem to appear randomly, when a particular school has deposited a more diverse and a coherent collection beyond the standard, statutory log books.

Internal school documents: Internal school documents produced from ‘above’ (e.g. sixth form guides, speech day programmes, timetables, and annual reports) cropped up in a variety of places. Sometimes they were free-standing items but more often they were pasted or tucked into log books and minute books. Sixth form guides are particularly useful as they show how staying on was marketed to pupils and parents by schools (e.g. one FAQ asked: ‘What if I don’t pass my exams – won’t it all be a waste of time returning to school?’), and can be read in conjunction with Governors’ minutes where available. Other documents are simply useful for fleshing out what log books tell you about the school’s corporate life with more detail, or providing basic information about the organisation and outward priorities of the school.

‘Bottom up’ school documents such as school magazines, school diaries, school work, and scrapbooks, are rarer than the top-down documents but, predictably, much more interesting. Scrapbooks and programmes are useful for fleshing out log book descriptions of school activities, especially when they contain photographs and pupil-perspective accounts. School magazines from comprehensive, secondary modern, and grammar schools appear in the archives unevenly, but they often contain revealing snippets of writing by pupils that provide valuable, subjective accounts of everyday life in the school.

Governors’ and PTA minutes: Governors’ minute books survive irregularly, and seem to be slightly more available for grammar schools. They provide a more detailed formal account of the business of schools than log books. A large part of their business is financial and relates to repairs, maintenance, and staffing. You will learn more than you ever wanted to know about the inadequate toilet and changing room facilities of UK secondary schools. They become more interesting around flashpoints, such as comprehensive reorganisation. PTA minute books are rarer than Governors’ minute books and slightly more interesting. Most entries relate to fundraising and the organising and running of PTA social events. However, when topics such as careers advice and exams arise, they provide valuable insight into parental concerns, especially if they are able to be used in conjunction with other sources.