By Bernard Barker

Bernard Barker is a former comprehensive school headteacher and emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Leicester. He was the first comprehensive school student to become headteacher of a comprehensive school. Bernard’s most recent books include The Pendulum Swings: Transforming School Reform (Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books, 2010) and, with Kate Hoskins, (2014) Education and Social Mobility: Dreams of Success (London: Institute of EducationPress, 2014). His educational autobiography covering the years 1946 – 1968, Busking Latin: from South London Comprehensive to Cambridge University, A Memoir, is due from The Stamford Press in October 2019. Contact Bernard to pre-order your copy. In this piece, he reflects on the intergenerational family conversations and relationships that shaped his educational pathway.

***

I hear my parents’ voices as I remember and write. In early summer 1957, I hurry home from school with the news I’ve passed the eleven plus (11+) examination. My parents are more relieved than pleased. Dad’s face is impassive, almost stern. Mother wants to know what happens next.

‘You’ll have to see Mr Offord, Bessie,’ answers Dad.

Mr Offord is headmaster of Kidbrooke Park Primary and expert on the 11+ and getting into local grammar schools.

‘I’m not happy with this interview business,’ she says, ‘From what I’ve heard they can be very picky.’

‘I’m not keen on grammar schools,’ says Dad with a frown.

This is a startling remark for a ten-year-old son to hear. I’ve taken the exam, I’ve walked the plank, I’ve squeezed through the closing door and now he doesn’t want me to go. Or does he? I say nothing.

In 1957 I do not know about my father’s own youth or understand his doubts. Dad attended Drayton Park, a London elementary school ten-minutes walk from his home at 9 Hartnoll Street, in Holloway N7. No one he knew ever won a scholarship to grammar school. Although Mr Palmer, the headmaster, wrote that young Chris Barker was ‘a splendid worker’ and ‘very intelligent’, the boy left in 1927, aged 14, and received no more formal education. In his mind, grammar schools are an alien life form, inextricably tied up with middle class airs and graces. But he is also imbued with socialist and trade union values and believes passionately in the power of education to change lives and bring about a more equal society. Dad is happy with his life in the Post Office, but knows things might have been different with qualifications.

‘I’m thinking about these all-in comprehensive schools,’ he says. ‘There’s no picking and choosing, everyone goes.’

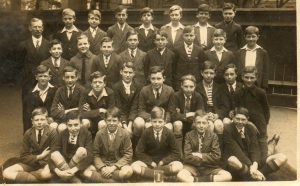

Above: Author’s father at Drayton Park School (second from left after teacher, back row), c. 1926. © 2019 Bernard Barker

Dad has followed the progress of nearby Kidbrooke School opened in 1954; Eltham Green, opened in 1956; and Crown Woods, too far from our house. The London County Council’s (LCC) modern palaces glitter with promise.

‘Nye Bevan says the common people are too obedient. He wants boys and girls like you, Bernard, to be more arrogant. You’ll be the masters now!’

Seven years later, I walk briskly home from school with ‘A’ level results in my jacket pocket and a smug expression on my face. Mother is in the dining room at the easel, studying her canvas. A matador waves a red cloak as he manoeuvres to thrust his sword between the bull’s shoulder blades. The scene is fashioned from geometric blocks of vivid red, black, gold and blue. Mother takes her palate knife and works a patch of dark red paint into a wound. Her intense expression becomes a lively smile as she greets me.

‘How did you get on?’ she says eagerly. But Mother knows my self-satisfied look so sets down the knife and grins.

‘B grades in English and History, with an E in Geography.’

‘What does that mean?’ she asks.

‘I’ll be able to get into the university of my choice,’ I reply, slightly irritated by the need to explain about sixth forms and universities. My parents are bright and knowledgeable but neither has travelled this path.

‘You’ll be able to sit the Cambridge entrance exam?’

‘Yes, but your chances are better with higher grades,’ I admit. There is also the little matter of Latin. ‘If I fail my “O” level re-sit, we can say goodbye to Cambridge,’ I add.

We look at the bullfight together. I tell her it’s good.

‘Mother, why did you leave school when you did?’

This is a difficult subject. She won an LCC scholarship to The County Secondary School Peckham and is a great advocate of education for her boys, but chose, nevertheless, to walk away from sixth form and university, even after passing the School Certificate in 1930, with credits in Geography, Arithmetic and Drawing.

‘The headmistress virtually begged me to stop on. Where does it lead? I asked. Teaching, she said. I didn’t want to be a teacher. Or a nurse, or a secretary! I wanted to join the Post Office like your Uncle Wilfred. He was earning money and had a lovely social life. I’d grown out of school.’

‘Do you regret it?’ I ask.

‘No, I enjoyed the Post Office counter, you meet human beings with amazing quirks every day, never a dull moment.’

‘But you wanted to be on equal terms with men, didn’t that make education important?’

‘I’m still fighting to hold my own,’ she interrupts.

‘You loved Bernard Shaw,’ I say, almost in reproach.

This irritates and angers her, a sore nerve.

‘I’ve lived in a houseful of men,’ she cries, ‘Your Dad, Wilfred, you and your brother, and I’ve never been a mouse. I’m not downtrodden or squashed. I fight my corner. And don’t imagine you’ll get away with anything silly, however big and important you become. I’ll be here and I’ll argue and put you in your place.’

I decide to let her get on with the bullfight and make for the door.

‘And don’t think it’ll make a difference if you get into Cambridge,’ is her parting remark.

Above: Eltham Green School, oil painting by David Williams. © 2019 Bernard Barker

Forty-two years later, I am in London for the last evening at 27 Woolacombe Road, the semi in Blackheath bought by mother’s family in 1938 and finally sold in 2006. The house is dark and cheerless. After weeks of clearing books, pictures, kitchen equipment and garden tools, only worn, faded furniture remains. Mother died in 2004 and Dad will not return from his nursing home. He talks but the words don’t make sense. But in this house my parents linger in the air. There are noises in the kitchen and I expect a steaming cup of instant coffee to appear soon. Upstairs, Mother’s scent drifts from an open jar of Marks & Spencer’s Royal Jelly on the bedside table. In the empty bathroom, I chant the six times table and imagine her quick hands rubbing my knees with a flannel. The sewing cabinet stands in a corner of the back room, with scissors, needles and thread ready to mend torn clothes. I sit at the dining table, gathering strength to leave but haunted by the sound of typewriter keys clattering in the bedroom above.

The telephone rings. Sue, my father’s carer, speaks softly.

‘How are you?’

‘Nearly done.’

‘How do you feel?’

‘Last one out, put off the lights.’

She pauses.

‘What time should I come?’

Sue has agreed to open-up for the house clearance firm in the morning.

‘They promised to come first thing, around nine,’ I reply.

This was the evening when the domestic scenery of my childhood and youth was finally torn away, the painful moment when the physical connection with my parents and their way of life was lost forever. But I wasn’t finished with education, even then.

Left: The author at Eltham Green School, c. 1958. © 2019 Bernard Barker

All text and images copyright 2019 Bernard Barker. All rights reserved. Please seek the author’s permission via email before quoting from this piece

Interesting…first met Bernard in the Spring term 1973 at Sir Frederic Osborn school where he held the post of Head of History. I was on interview. He had introduced some super and forward-looking methods into the teaching of that subject and was extremely enthusiastic! Unfortunately Bernard did not rate me, letting the ‘cat out of bag’ when discussing the merits of the candidates for that job with a colleague in the toilets before the interviews which I overheard. Never mind. Later on I was grateful for Bernard’s advice when I was promoted myself to head of department in a neighbouring authority.

Bernard has consistently been over a long and successful career a very sensible, respected and well informed commentator on educational matters.

Bernard taught me at Sir Frederic Osborn school 1974-77.

He encouraged debate: instead of belittling my teenager views on the existence of little green men (I was reading Erik von Daniken at the time) he turned the class over to me and we argued point-by-point. I was cheered on my by classmates (presumably for my daring to question – it certainly wasn’t the cogency of my arguments !), but I took away a deep sense of being valued, of being respected, of having a voice that I would have to then justify.

He paid incredible attention to his students’ work. My essays came back hugely annotated in red pen: not just corrections, but also long comments, suggestions and encouragement. Multiple whole sentences at the end blew me away … I was used to just getting a mark “X/10” and maybe one single word. I was encouraged & did more.

He encouraged students to apply to Oxbridge, supported, encouraged and helped. We had to take an entrance exam a year earlier than the pubic school kids, so Bernard laid-on some extra tutoring … at his house, in his own time. Six of us got in. Amazing. All these ordinary kids went off to mingle with the toffs.

My sister is 3 years older and went to the same school. Her experience was totally different from mine: the school was poor. that failed her. My experience was of a vibrant, exciting school, albeit with a few duff teachers. A huge part of the difference was Bernard Barker.

I am still struck by how one single person can make such a difference (appointed by the Head, who had the vision to bring in, and fully support, such a person).

I have just read your interesting article. I started the school the same day as you and we were in the same class. I remember Mr Maynard the English teacher and Mr Murphy the maths teacher who lived near me on the Sidcup road