By Charlotte Lauder // Charlotte is a final year AHRC-funded PhD student at the University of Strathclyde and the National Library of Scotland. She focuses on popular literary magazines produced in Scotland between 1870 and 1920.

School magazines are a significant (and often overlooked) feature of educational print culture in modern Scotland. They take many forms – most were printed annually by schools to provide an update on pupils’ activities and the school’s progress. Some magazines were handmade by pupils. The Museum of Childhood in Edinburgh has an excellent collection of manuscript magazines made by children (though not all by children at school), including Talks and Tales (1911-16), created by a teenage Christine Orr (1899-1963), who later became a prolific novelist, playwright, and theatre activist. The National Library of Scotland has a large collection of school magazines, serials, and periodicals which I spent time consulting during a work placement at the Library last year.

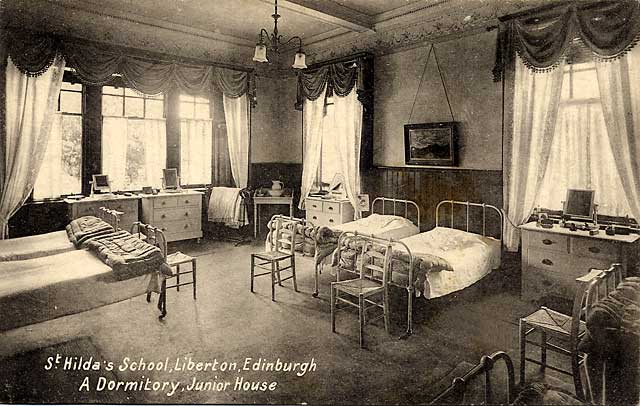

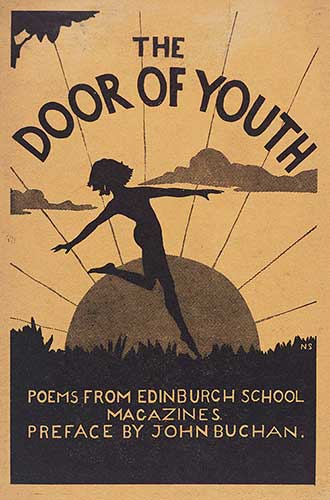

There are handmade magazines, supplementary magazines, school directories, and literary magazines, such as The Door of Youth (1930) [image 1], a collection of poems collated from Edinburgh school magazines, and includes five poems by twelve-year-old Muriel Camberg, later the acclaimed author Muriel Spark (1918-2006), whose poetry was first published in James Gillespie’s High School Magazine whilst she was a pupil there. The Library also has magazines from a variety of education unions and associations, such as The Educational news (Educational Institute of Scotland) (1876-1918), The Shorthand teachers’ magazine (Society of Certified Teachers of Shorthand) (1910-12), and The Scottish schoolmaster (Scottish Schoolmasters Association) (1935-75). Other kinds of school magazines include rolls of honour and memorial volumes detailing pupils and alumni involved in the First and Second World Wars [image 2]. The Library has digitised and made available online the rolls of honour of several secondary schools in Scotland, and has digitised exam papers for the School Leavers Certificate (1889-1961), the Scottish Certificate of Education (1962-63), and a variety of school materials are available open access via its digital gallery and Data Foundry.

An early example of a school magazine created by children is The Satchel (1866), which was created by the boys at the Edinburgh Institution (now Daniel Stewart’s College) as a ‘a miscellany of entertaining reading […] for the recreation of the pupils’. It appears to have been fairly popular – in the magazine’s last issue, the boys describe that ‘100 constant subscribers have honoured us by looking over its pages’. A similar magazine was produced by the girls of Class I at the Edinburgh Ladies’ College (now the Mary Erskine School) in 1877, which is held in the collection of Janet Logie Robertson (née Simpson) (1860-1932), who edited the magazine as a pupil. ‘Our Magazine’ intended to ‘afford a means of relaxation from the graver subjects which are supposed to engross the most of the pupils’ attention’, and is a unique assortment of reflective articles, original poetry, travel essays, and illustrations by the girls, delicately drawn over the lines of the printed jotter-paper. These self-produced children’s magazines were common in the late-nineteenth century and are an important insight into representations of childhood in a school setting.

What about school magazines in the twentieth century? Impressively, several schools in Scotland consistently published magazines over the course of the twentieth century. The Library has a run of The Dollar Magazine (Dollar Academy) from 1902 to 2001, the Glasgow High School Magazine from 1906 to 1990, The Broughton Magazine (Broughton High School, Edinburgh) from 1909 to 1971, and the Inverness Royal Academy Magazine from 1925 to 1992. Magazines with long runs such as these offer an opportunity to trace changes in educational practice and differences in the expression of life at school throughout the twentieth century. [images 3, 4, 5]

The Library’s collection has a wide geographical scope. Although most of the magazines were published in Edinburgh and Glasgow (Scotland’s most densely populated areas with the highest number of secondary schools), there are magazines from almost every local government area in Scotland between 1920 and 1990. Several are from schools in the Islands, such as The Kirkwallian (Kirkwall School, Orkney), the Portree Secondary School Magazine (Portree High School, Skye), and Bowmore J.S. School Magazine (Bowmore J.S. School, Islay). Since regional identity remains an under-researched area of modern Scottish history, research into these magazines, including comparisons with magazines from Highland or Lowland schools, might provide an interesting framing for how modern regional identities are expressed by (and taught to) school children.

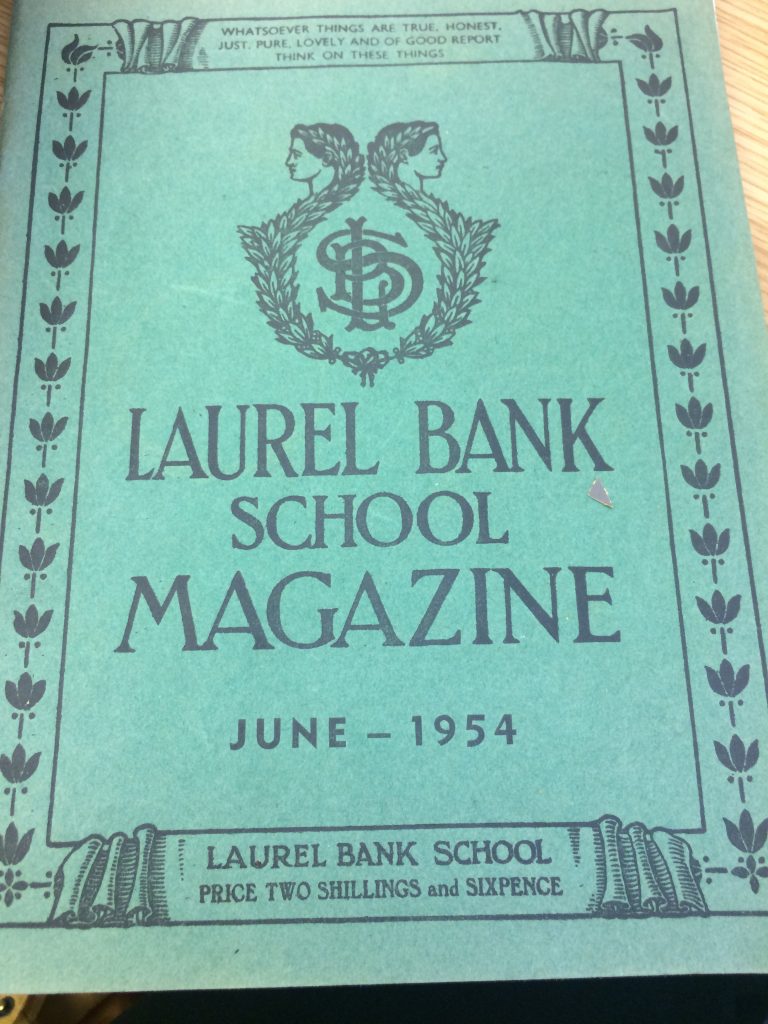

The magazines also shed light on schools and institutions that have been lost to time. Between 1912 and 1940, three magazines were produced by St Hilda’s School, Edinburgh, which, despite growing up in Edinburgh, I had never heard of. St Hilda’s opened in 1901 as a girls’ boarding school in a large Victorian villa in Liberton, Edinburgh, and at the outbreak of the Second World War the girls were evacuated to Ballikinrain, Stirlingshire [image 6]. Though the school is long gone, magazines like The Saint Hildan (1912-37) are an important resource in the recovery of institutional histories and secondary schools in Scotland.

Although the magazines in the Library are well-balanced between private and state schools, magazines published by state schools dominate the collections in the post-war period, most likely a result of secondary school expansion after the Education (Scotland) Act of 1945. Indeed, where most private schools follow a traditional format and layout in each issue – featuring the school’s crest, familiar illustrations, marginalia, and fonts – originality is more indicative of state school magazines. For example, pupils at the Royal High School in Edinburgh produced their own literary magazine called Phaeton in 1956-7, and the Philatelic Society at Aberdeen Grammar School published a magazine for its members in 1923-4. Similarly, the front covers of some magazines in the 1960s and 70s feature contributions by pupils, which reflect different mediums (and artistic ability) like photography, collage, and watercolour. In a non-digital era, when print culture was still the primary source for creativity and imagination in schools, these magazines provided a much-needed output for children’s literary expression. Similarly, school magazines were genuine evidence of a pupils’ productivity when communication between school, child, and household was much slower and educational accountability a less stringent prerequisite for parents.

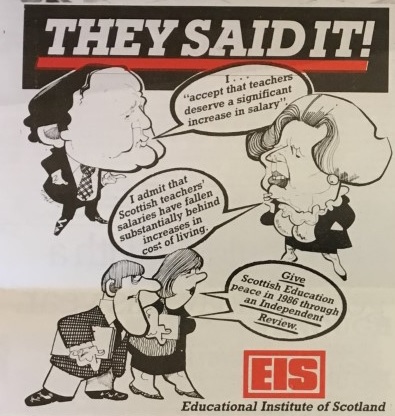

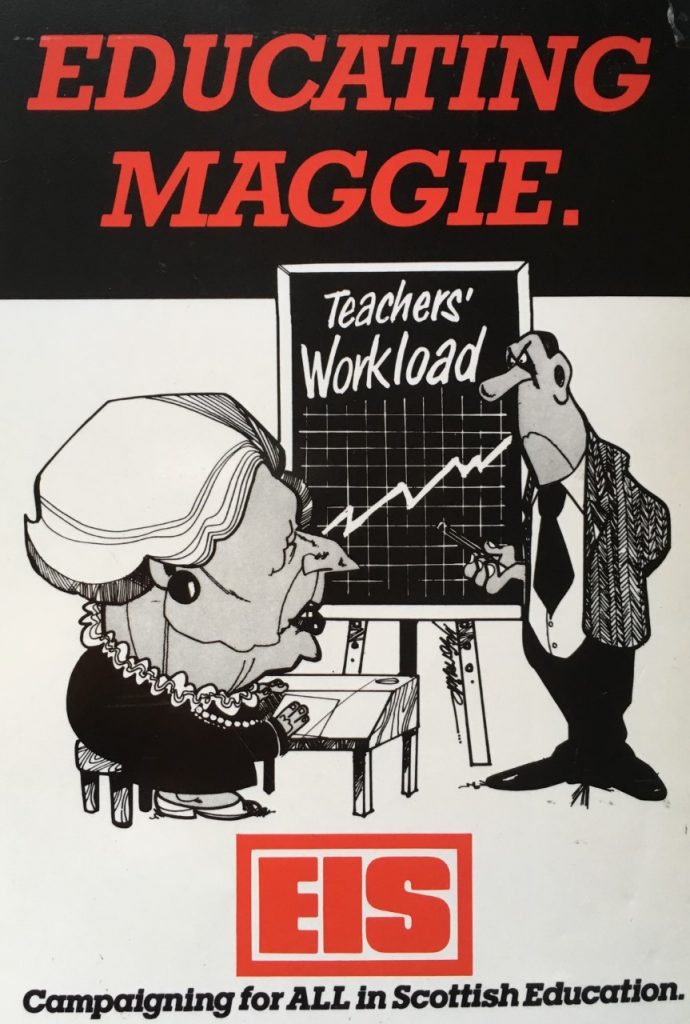

Finally, the Library also holds copies of magazines for teachers, such as the Scottish educational journal (1918-) which is the monthly organ of the Educational Institute of Scotland, the country’s largest teaching union. The magazine’s issues in the 1980s reflect the politicisation of Scottish education and chart the development of the teachers’ strikes in 1985 that protested the education cuts enacted by the Thatcher government. Images are an important feature of these issues and cartoons convey satirical, yet serious, depictions of the tense relationship between the UK government, teachers, and Scottish education [images 7 and 8]. There are interesting discussions about the autonomy of Scottish education in these issues, something which scholars of Scottish devolution, politics, and trade unions since the 1970s might be interested in pursuing.

Ultimately, school magazines are publications with a porous boundary between consumption and contribution, and represent a form of reflective communication and creativity that was extremely popular in the postwar school environment. They can convey an interesting dynamic between local, regional, and national identities in modern Scotland and how closely these identities are bound to the institutional histories of secondary schools. Educational records are some of the largest deposits in the collections of archives, libraries, and museums across Scotland and continue to be a vibrant area of contemporary collecting. Material relating to schools encourages lively engagement from members of the public which can only grow with the continued focus on widening access and digitisation at the National Library of Scotland. From Stornoway to Swinton, there are countless issues of school magazines that await readers’ attention, which can hopefully resume once we are able to return to public buildings.

A fascinating account. The examples which Charlotte cites reminds me of my own foray into the genre that she analyses, co-editing the magazine in the school which I attended (Tain Royal Academy, in eastern Ross and Cromarty) in my final year there, 1973-4. This was at the height of the first impact of the oil boom, which had massive effects on the social infrastructure of Easter Ross, as elsewhere in the Highlands. Large manufacturing plants were very rapidly established in what had been an economically stagnant rural economy, attracting much in-migration, mainly of men (with their families) whose job prospects were precarious in the already declining manufacturing industries of central Scotland and northern England. This economic vibrancy also seriously disrupted local businesses, which lost staff to the new industries because they could not afford to pay the wages that the oil companies could offer. Spontaneously, pupils in the school that year submitted poems, short stories, drawings and many other reflections on what social scientists would call social change and modernisation. The tone was strikingly optimistic, welcoming change, diversity, and new opportunities. Because this moment also coincided with the first strong emergence of Scottish nationalism, stimulated by the discovery of oil, themes of identity ran through these contributions: the perceived loss of an old Highland culture, the radical ideas of the 7:84 Theatre Company’s massively popular play, The Cheviot, The Stag and the Black, Black Oil, and the intersecting debate, which remains intense to this day, between questions about Scottish self-government and questions about social reform. Re-reading these contributions now, I’m struck by how strongly they anticipated social debates that are still with us now. The study of school magazines, after all, is an investigation of the emerging minds of the future.

Thanks for your kind words, Lindsay. I remember your lectures on modern Scottish history during my undergraduate at Edinburgh, and enjoyed how important education was to those discussions. As you say, there’s far more to uncover about the connections between nationalism, regionalism, and industrialisation in educational print culture. I’m sure a study of the Tain Royal Magazine would be very helpful here!

We had a very fine school magazine at St Ninian’s High School in Kirkintilloch, edited mostly by the Head of English Patrick Kearns and well produced on glossy paper. It carried pupils’ stories and essays, many of them quite boldly satirical for the time (c.1964-68) , and the first published poetry by myself , Gerard Mulgrew and James McGonigal (c.1964-67).

Looks most interesting. There are many Public School magazines online which provide invaluable information about them during the Great War. in the absence of official files. Looking at these magazines will widen up a study of what they shared and where they differed in their approach and and attitudes towards the war.