By Laura Tisdall //

Dr Laura Tisdall has just completed the first year of a three-year Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship in History at Queen Mary, University of London. She specialises in the histories of childhood, adolescence and education in modern Britain.

***

In 1963, a fifteen-year-old school girl recalled, in an essay titled ‘Myself at 10’, how it felt to be five years younger:

I was not helped… by many adults who treated me as a child… children can understand far more, and far more complicated things, than is generally realised, and do not appreciate people who say “Oh, you wouldn’t understand dear, now shut up,” and go on nattering to Aunt Flo… Many of the people who used this tone fancied themselves as managers of children, and were determined that we would remain children, to their stereotype, until they decided we had suddenly grown up. [1]

This essay was part of the English Writing and Composition Project run by the Institute of Education; in the strand in which this pupil was participating, groups of pupils from particular schools were asked to write essays at six-month intervals over the course of two years, so the researchers could trace the development of writing ability between the ages of fourteen to sixteen. The essay titles appear to have been fairly arbitrary, perhaps selected on the basis of what the researchers thought would ‘interest’ teenagers. (This was not necessarily a successful strategy: one respondent wrote, in frustration with the latest assignment, that it was ‘the worst, most uninspiring collection of titles I have ever seen’. [2] )

Looking at how children and teenagers wrote about age when they were still under eighteen, rather than focusing on adult memories of childhood and adolescence, is crucial for historians who want to analyse these age-categories. Unlike other identity categories such as gender and race, age is unique in being an experience that everybody shares, and yet also an experience that everyone loses. While all adults were once children, they are no longer children, and so can no longer speak from this subordinate social position; as Carolyn Steedman has written, ‘the child grows up and goes away’. [3]

These essays, one of the source sets I’m using for my Leverhulme-funded project ‘Adolescents’ concepts of age and ageing in Britain, c.1950 to the present day’, allow us to see how children and teenagers interacted with new psychological and psycho-analytical ideas about age in post-war Britain. Obviously, they do not grant us unmediated access to what these writers ‘really’ thought about age; they were written in a classroom, under the supervision of a teacher, for a distant research project that their writers knew little about. However, they do indicate what teenagers thought they ought to write about growing up, and that they understood what they were doing when they challenged this received wisdom.

My previous research has shown that developmental psychological ideas about age profoundly affected both primary and secondary modern school teachers’ concepts of childhood in England and Wales from the 1950s onwards. [4] Adolescents were refigured as cognitively incapable of logical thinking, positioned as innately impulsive and reckless because of their inability to plan long-term. Their limited empathy also suggested that they were likely to be selfish and self-centred. These characteristics were linked to a maturational concept of developmental stages that was communicated to teachers through popularised versions of the work of Jean Piaget, suggesting that adolescents could not overcome these defects by conscious effort, but became more capable simply by getting older.

Teenage pupils, while often concurring with this characterisation of adolescence through the use of psychological language, were less likely to assume that it applied to all individuals who shared a chronological age, or that adolescents were unable to behave differently while they remained in their teenage years. A significant number of respondents to the Institute of Education study emphasised that the negative connotations of adolescence did not apply to them because they were ‘not like other teenagers’, a strategy which entailed stigmatising their peers. One respondent, writing on the anti-nuclear Aldermaston marches, argued that:

It is a well known fact that certain teenagers join every political society in their city, and then use them as “glorified Youth Clubs” without knowing anything of their views. This makes a mockery of it all. Much as I regret to say it the main disturbing influence of demonstrations of this kind in England is the teenagers. [5]

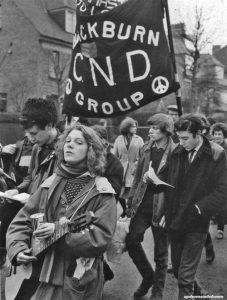

Left: Young people on one of CND’s ‘Ban the Bomb marches’ to Aldermaston, March 1963. ©Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Conversely, other teenage writers used the threat of nuclear war to emphasise the failure of their parents’ generation, implying that adults had abdicated their natural authority through the development of the H-bomb. Writing in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, one respondent, in an essay on ‘What are some of the commonest causes of disagreement between young people of your age and their parents?’, wrote:

Some young people dislike the older generation because of the threat of Atomic war they feel, and rightly so in my opinion, that it was the old scientist of years ago that gave us this threat because of their childish instinct to create things that cause mass destruction. [6]

The employment of the language of age here positioned adults as ‘childish’, flipping the usual power dynamics. However, this writer also used another rhetorical strategy found in a number of other essays, arguing that the supposed ‘irresponsibility’ of teenagers, exemplified by their lack of financial planning, was actually a rational response to the situation in which they found themselves:

Mabye [sic] they feel we should save the money, for we will need it on a “rainy day” but what they don’t realise is that there might never come a “rainy day” with the threat of Atomic war. [7]

Post-war psychological ideas about the innate irresponsibility and selfishness of adolescence were not only well-known to these teenage writers, but were weaponised by them: either to emphasise that they were not really ‘adolescent’ because they were serious and responsible; to suggest that adult treatment of young people actually forced them to ‘remain children’; or, perhaps most creatively, to contend that adolescents didn’t plan for the future because the older generation had ensured they weren’t going to have one.

[1] English Composition and Writing Project, Institute of Education, WRI 1/1/1, essay 139.

[2] English Composition and Writing Project, Institute of Education, WRI 1/1/8, essay 286.

[3] Carolyn Steedman, Childhood, Culture and Class in Britain: Margaret McMillan, 1860-1931 (London: Virago, 1990), 79.

[4] Laura Tisdall, A Progressive Education? How Childhood Changed in Mid-Twentieth-Century English and Welsh Schools (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019)

[5] English Composition and Writing Project, Institute of Education, WRI 1/1/1, essay 3.

[6] English Composition and Writing Project, Institute of Education, WR1 1/1/2, essay 257.

[7] Ibid.