By Annie Thwaite //

Love it or loathe it, homework is, and has long been, an important part of secondary education. This year’s nationwide school closures have meant that children were (and in some cases are still) being taught from home, bringing a whole new meaning to the word ‘homework’ (alongside another, older meaning, associated with mostly female at-home workers, which the historian Helen McCarthy has recently written about here). This prompted us to delve into the archives and consider the pupil and parent experience of homework in the UK since 1945. In addition, the recent need for emergency remote learning has acutely highlighted many of the longstanding social issues surrounding doing school work at home, for example, finding a quiet space to work in busy households. This blogpost explores homework in the SESC archives and beyond, and asks: what are your memories of homework?

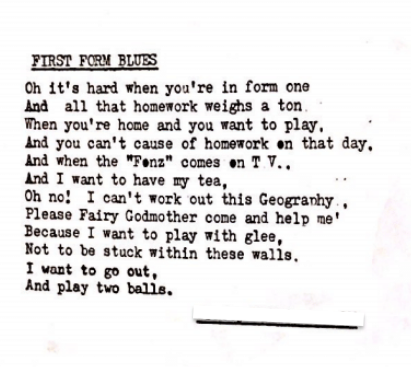

Homework has generally been seen as an important part of learning, given to ensure that pupils can practice and improve upon what they have learnt in lessons, and get the most out of the particular subject they are studying. It might also be seen to encourage good habits of independent, unsupervised work and other useful attributes for later life, preparing pupils to enter the workplace. As secondary education expanded from 1945 onwards, homework also expanded to include different subjects and different social groups, becoming increasingly common and increasingly important. But while given in pupils best interest, homework has often been met with resentment and displeasure by all those who have had to do it, and help with it. Indeed, entrants to Merrywood Boys’ Grammar School, Bristol in 1981 were told that they were expected to give their homework ‘proper care and thought, remembering that it is given in their interest’; perhaps as a reminder to students like this Year 7 from Fitzalan High School, Cardiff, who wrote a morose poem about his homework in the 1977 edition of the school magazine, lamenting that ‘homework weighs a ton’.

Yet while most (although not all) children were divided by the 11+ exams between grammar schools and secondary modern schools (and their equivalents in Scotland) after 1945, the experience of homework initially differed greatly according to individual schools and school types. Peter Gordon has noted how in grammars, homework was a more accepted part the course of education, whereas practices in secondary modern schools varied significantly.[1] According to a survey of male pupils carried out by the Central Advisory Council for Education, England between November and December 1947:

- 24% of secondary modern boys in the survey were given up to an hour’s homework each evening, in contrast to 43% for grammar school boys

- Just 5% of secondary modern boys compared to 55% of grammar boys did more than an hour’s homework

- And 71% of secondary modern boys compared to 2% of grammar boys had no homework at all.[2]

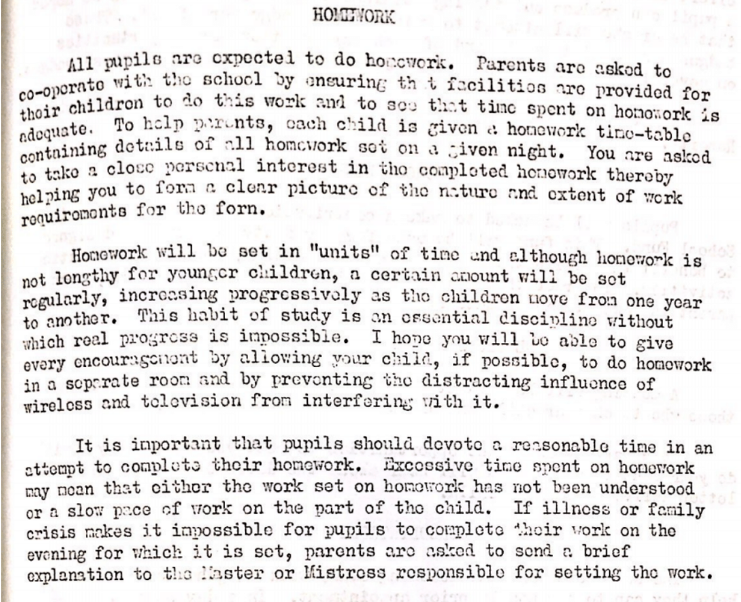

Whatever the level of homework given, it soon became necessary for pupils, parents and teachers to keep track of homework and ensure its completion. School guides for new pupils have almost always made reference to the timetables and planners that would guide student’s homework. For instance, new parents and entrants of Llanedeyrn High School in Cardiff in the 2000s were told of the importance of the pupil planner and homework timetable in recording homework, the guide noting that:

- ‘The planner provides an important means of communication between home and school. Every week we ask parents/carers to sign the Planner. The Form Tutor will also sign the Planners regularly.’

- ‘To help parents, each child is given a homework time-table containing details of all homework set on a given night. You are asked to take a close personal interest in the completed homework thereby helping you to form a clearer picture of the nature and extent of work requirements for the form.’

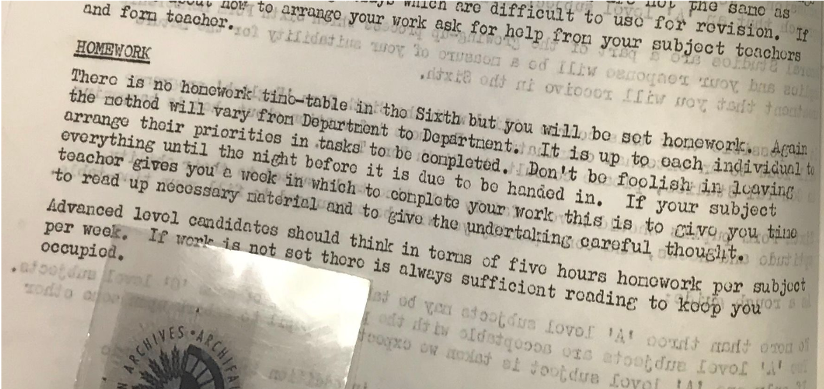

As pupils progressed upwards in school, these more rigid means of tracking and assessing homework might be dropped; students entering sixth form at Llanedeyrn in 1975, for example, were informed of their new responsibilities regarding independent study, but warned not to rush homework ‘the night before it is due to be handed in’.

Meanwhile, staff had their own responsibilities surrounding the proper completion of homework. Teachers at Merrywood Boys’ School in 1974 were told to: look through a boys written work and homework so that you know the standard being achieved and can follow up poor or omitted sections. Particular attention here to neatness and presentation. In the event that students had failed to complete homework, teachers might dole out penalties. The records of Fitzalan Technical High School Punishment Book in the 1960s demonstrate how ‘Persistent refusal to do homework’ might result in corporal punishment:

18.10.61, Male pupil (2C), Persistent refusal to do homework, 2 strokes on each hand by a teacher

16.2.62, Male (1B), Persistent refusal to do homework, 2 strokes on rump by a teacher

Homework might even be given as punishment for other forms of bad behaviour in school. The minute book for the school council of Braehead School, Aberdeen in 1957 recorded the punishment given to a female student playing truant as catch-up homework:

11/12/1957: The question was raised about [female student] playing truant and then giving Miss X a note that was of her being absent about a week ago. The Council decided that she should get homework from the teachers she missed on the day she played truant.

If homework was crucial to a pupils subject knowledge and self-development, what form was it to take? The Essex Education Committee set out its views on this matter in a 1954 journal issued to the county’s schools.[3] According to the Committee, there should be two types of homework: formal and informal. As the majority of pupils stayed for only four years (ages 11-15), formal homework was given in the attempt to cover everything they wanted to in school, particularly for English and Maths.

A certain amount of relief could be afforded to a very full curriculum and higher standards achieved if some time were given to study outside regular school hours.

Essex Education Committee, 1954

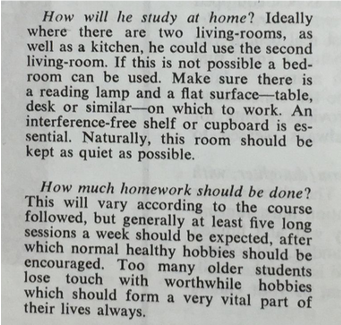

Informal homework however could align with pupil’s own personal interests, whether they enjoyed craft-work, photography, collecting, or any of a range of other activities. By 1971, many of the same attitudes to the different types of homework appeared to have been retained. The CASE (Confederation for the Advancement of State Education, Essex) handbook entitled Local Schools: A Handbook for Parents from 1971 discussed ‘staying on’ for sixth form, and noted that pupils should do five sessions of homework a week, but flagged the vital importance of healthy, worthwhile hobbies.

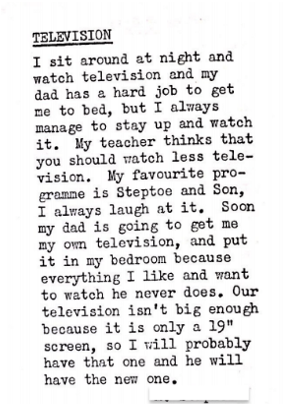

Forms of entertainment, however, might well be prove a distraction to pupils trying to do their homework. From the onset of universal education, homework was impacted by new forms of technology in the home. In 1948, the Ministry of Works commissioned a survey in Merseyside on the effects of the radio, which noted that less than half the children could say that they did not hear the wireless at all, and 1 in 8 heard it all the time. A decade later, a Nuffield Foundation study on Television and the Child examined two commonly held sets of views: 1) that television interfered with homework and serious study, but 2) that on the other hand television encouraged new interests and so made the child more willing to take certain subjects seriously.

The potential distraction caused by radios and TVs was reflected in school guides, such as the booklet of Information for Parents of New Entrants at Llanedeyrn High School from the 1970s, which implored parents to:

give every encouragement by allowing your child, if possible, to do homework in a separate room and by preventing the distracting influence of wireless and television from interfering with it.

The issue of distractions in the home links to a much broader social issue, as while parents could be asked to provide suitable working conditions for their children to do homework, these demands were inevitably limited by the dynamics of individual home environments, social class, gender, age, ethnicity, local geography, and the tendency for pupils to have afterschool and/or Saturday jobs. [Read more about the relationships of parents to education in this briefing paper by Dr Chris Jeppesen]. The requirement for emergency remote education from March this year highlighted the need to understand the complex and varying needs of children’s lives away from school. Articles in the media emphasised how many families in the UK don’t have access to the technology necessary to facilitate home learning through computers, tablets or printers, or even paper and writing equipment. According to a report by the UNESCO Education Centre at Ulster University, while many parents spoke positively about home-based learning, others described difficulties in navigating online resources, and parents of children entitled to free school meals were more likely to have no or poor internet access compared to other parents.[4] Meanwhile, an estimated two million children in England live in homes affected by substance abuse, domestic violence or mental health issues.[5]

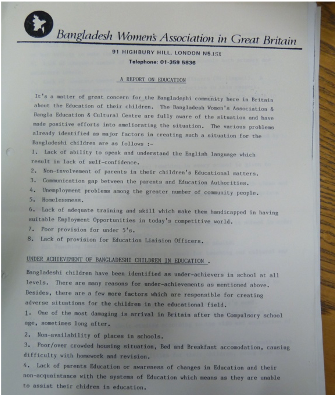

These complex social issues concerning the relationship between home life and school work are longstanding. One of the earliest longitudinal studies into education and inequality after the Second World War found that it was the home context that determined children’s ability to succeed in the education system.[6] A report by the Central Advisory Council in 1963 on ‘the education of pupils aged 13 to 16 of average or less than average ability’ found that in many urban areas, the conditions in which some families lived made it impossible for homework to be done satisfactorily. The report urged quiet rooms in schools and public libraries to be provided if all pupils were to successfully complete homework.[7] Similarly, a report by the Bangladesh Women’s Association in Great Britain examined the difficulty pupils faced when doing homework in poor and overcrowded accommodation. Other issues such as difficulties with language, mother’s and father’s lack of education, and work schedules meant that parents were unable to support children with their education, leading to under achievement of Bangladeshi children in education.

In its 1977 report, the Commons Select Committee on Race Relations and Immigration highlighted extensive concerns about the poor performance of West Indian children in schools, and recommended that the government should institute a thorough independent inquiry into the causes of underachievement. Labour education secretary Shirley Williams established the ‘Committee of Inquiry into the Education of Children from Ethnic Minority Groups’ in March 1979. The Committee published its interim report West Indian Children in our Schools, or the Rampton Report, in 1981. It concluded that the main problems were low teacher expectations, and racial prejudice among white teachers and society as a whole; yet this message was widely unpopular, and attacked by the media before the report was even published.[8] Under a new chairman, the Committee’s final report, the 1985 Swann Report entitled Education for All mostly repeated Rampton’s conclusions, including that:

- LEAs and schools should look for ways in which parents can be more closely involved in helping their children learn to read, and teachers should be better trained to understand the language needs of ethnic minority children

- LEAs should ensure that information is provided in a form which is accessible and easily understood by parents, particularly those from ethnic minority groups

- Schools should encourage teachers to see home visiting as an integral part of their pastoral responsibilities

- LEA induction programmes for probationary teachers should include guidance on the needs and backgrounds of all pupils in their area

Altogether, it seems that homework is about more than just making school children to spend more time studying. Instead, it represents the expansion of educational practices into the home, which has made us as a society increasingly aware of how uneven the playing field is for children in schools, due to the diversity of home circumstances. One marker of this might be seen in the way that the guides and parent handbooks created by schools from the 1970s and 80s increasingly attempted to detail their expectations about homework directly to parents (like in the examples above, from Llanedeyrn High School) – perhaps an attempt to establish and standardise good habits across families in the school community.

What are your memories of homework? Do you recall struggling through the subjects you found trickier, or do you have clearer memories of the more fun, ‘informal’ homework like the kind described in this post? Did the TV or radio distract you from work, or would you have liked even more homework to do? Let us know in the comments below.

[1] Peter Gordon (1980) Homework: Origins and Justifications, Westminster Studies in Education, 3:1, 27-46, p.41.

[2] WARD, J. (1948) Children Out of School. An inquiry into the leisure interests and activities of children out of school hours carried out for the Central Advisory Council for England in November-December 1947, p.23 (London, HMSO)

[3] Homework in secondary modern schools, Essex Education, 8, 1954, pp.7-8.

[4] Online child abuse rising during lockdown warn police, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-52773344; Coronavirus lockdown ‘perfect storm’ for abused children, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52876226; Vulnerable children will ‘slip out of view’, commissioner warns, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-54159977 [all accessed 23/09/20].

[5] Coronavirus: ‘2m children face heightened lockdown risk’, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-52413511 [accessed 23/09/20]

[6] J.W.B. Douglas The Home and the School (1964)

[7] MINISTRY OF EDUCATION (1963) Half Our Future. A Report of the Central Advisory Council forEducation (England), pp.41-2 (London, HMSO); Gordon (1980) Homework: Origins and Justifications, Westminster Studies in Education, p.42.

[8] The Rampton Report (1981), ‘West Indian Children in our Schools’, http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/rampton/index.html; The Swann Report (1985), ‘Education for All’, http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/swann/index.html.