This blog was originally written by former SESC Research Associate and continuing SESC collaborator Dr Laura Carter, for the LARCA Gender and Sexuality Studies research group blog at the Université de Paris, where she now works.

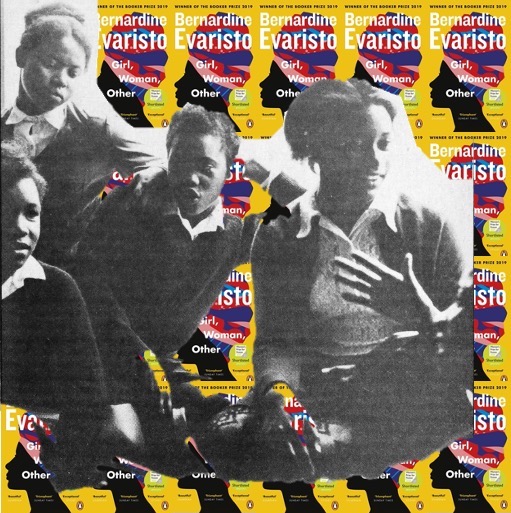

Bernardine Evaristo’s 2019 ‘fusion fiction’[1] novel Girl, Woman, Other introduces several familiar narratives about postwar education in Britain: the ‘golden age’ of the grammar school, the myth of education as a route to social mobility, and the ‘failure’ of the comprehensive school. In each of these cases, Evaristo repositions the narrative by revealing them through the eyes of (mostly) girls and women of colour. In this blog post, I’ll explore the place of the secondary school in Girl, Woman, Other. I’ll also suggest a few things that historians might learn from Evaristo’s fictional, intersectional, and intergenerational perspective on the postwar secondary school.

Just like in most stories of everyday life set in twentieth-century Britain, school days feature prominently in Girl, Woman, Other. We first catch glimpses of the New Cross girls’ grammar school where Amma and Shirley are the only two black pupils in the 1970s. They forge a lasting connection through this shared experience of schooling, despite the vast personal and political differences that will develop between them. One semi-fictional London secondary school in particular, ‘Peckham School for Boys and Girls’[2], is our mooring point as we follow the lives of the interconnected suite of characters in the novel. This Peckham school is the ‘multicultural zoo’ of my title, a racial slur used by teacher Penelope to signify its shift from white working-class uplift to postcolonial, multi-racial education.

The school is a co-ed comp, where Shirley, first introduced to readers as an ambitious young black teacher, begins her career in the 1980s and where she encounters racist Women’s Libber Penelope, who is already mourning the loss of her 1970s dream for the comprehensive school. It’s also the site of Carole and LaTisha’s troubled school days of the early 2000s, by which point the school is on the brink of failure, plagued by knife violence, drugs, and teen pregnancy. This view across the decades is particularly powerful in driving a key message of Girl, Woman, Other: for this particular set of characters, secondary school is a site of almost universal disappointment.

This disappointment comes in various forms. Carole finds the strength within herself to move past her horrifying experience of rape and turns to Shirley (by this point known, at best, as the ‘School Dragon’) as a mentor. Carole uses the school exam system to attain upward social mobility first via the University of Oxford and then the City of London. But there is no warm and fuzzy place in her heart for her old school, indeed Carole’s awkward encounter with Shirley at book’s end suggests how plainly functional institutions (and their staff) are in Carole’s self-narrative. As a highly intelligent and highly successful black woman operating in all-white spaces, Carole’s inner drive and well-honed survival tactics lift her out of poverty and trauma, at great personal cost with respect to her Nigerian heritage. This is quite different to the celebrated narrative of the white working class, upwardly-mobile grammar school boy, who returns home to pay his social and cultural capital forward.

We meet Carole’s one-time friend, LaTisha, also climbing the ladder of social mobility (in her words ‘on the move’), working her way up the management hierarchy in a local supermarket. At their comp, LaTisha was part of what 1970s sociologists would have called the ‘counter-school’ subculture. LaTisha makes some very poor choices, but she is also highly intelligent, evidenced by her precocious, but logical retorts to each ‘senseless’ school rule she encounters. The school fails her too, by presenting her black girl future as a fait accompli. The school has no resources, no energy, no willpower to accommodate LaTisha’s complex social and emotional needs, and she’s unwilling to assimilate to the ‘good girl’ codes like Carole does.

As we learn from both Penelope and Shirley’s narratives, the social justice mission of the comprehensive school is a faded memory by the 2000s in this corner of South London, and the long-standing racialisation of social problems located in the comprehensive school is a burden that girls like LaTisha must bear at the beginning of the new millennium. Earlier echoes of this shift appear in snippets of LaTisha’s father’s story, a first-generation immigrant pupil from the Caribbean who found himself thrown in the ‘Sin Bin’ for speaking patois (presumably in the 1970s).

Shirley and Penelope, the two teachers, are also deeply disappointed by the secondary school they work at. For Shirley it’s the educational reforms of the Thatcher governments that curtail her pedagogical freedoms in favour of box ticking and league tables, whilst Penelope sees multiculturalism as a monster that swallowed second-wave feminism whole within the school gates. This shared disappointment leads to a cautious pact between the two women (they are ‘work friends’ according to Penelope), suggesting how age might work to reconcile white and black feminisms. But their alliance isn’t forged in a shared, positive commitment to intersectionality. Instead, the bleak landscape of the late-century, failed comprehensive school in which they both toil as older, disillusioned teachers bridges their cultural divide.

Racial justice becomes less important to Shirley as she grows older and faces fewer daily micro-aggressions in the staffroom and classroom. At mid-life, she finds personal satisfaction more in the material and emotional spoils of family life, settling for occasional, individual success stories like Carole’s, rather than the structural, political changes she yearned for as a newly-minted teacher. Shirley is essentially a conservative character; she embraces her embourgeoisement and nurtures a little germ of nostalgia for the Butler Act of 1944.

The intergenerational framing of Girl, Woman, Other brings the racialised and gendered aspects of English comprehensive education between the 1960s and 2010s into sharper focus in ways that are quite helpful to historians to think with. For example, Evaristo strongly foregrounds sexual harassment and sexual violence towards girls by both peers and teachers, an issue that historians might find difficult to reconcile with a still rather fixed narrative of postwar British history in which ‘comprehensivization’ is aligned with progress. Secondly, Penelope’s racist caricature of the school as a ‘multicultural zoo’ signals the rich, discursive history of multiculturalism in British education that remains to be excavated.

Finally, the black and mixed-race characters found in this book are excellent, if sometimes composite, avatars for thinking about how individuals might have negotiated the mixed ability, co-educational, and multi-racial spaces of the postwar comprehensive school. To succeed, Carole must assimilate and credentialize, LaTisha must fulfil her ‘teen mom’ destiny, and Shirley and Penelope must relinquish their respective social justice missions. This combination of pragmatism, alienation, and a hint of possibility are useful starting points for mapping the social and emotional landscape of the British comprehensive school since the 1960s.

[1] Bernardine Evaristo, ‘Words of Colour’ Waterstones Library Bristol Takeover, 10 March 2020 [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mu8Yo6i6VdU].

[2] Possibly modelled on Warwick Park School in Peckham, an 11-16 mixed comprehensive which closed in 2003 and became an academy.